By Richard Alford, a former New York Fed economist. Since then, he has worked in the financial industry as a trading floor economist and strategist on both the sell side and the buy side.

Five years after the financial crisis and halfway to a lost decade, economists, policymakers and the public are looking for answers that will restore economic health and vibrancy. Their concern has increased recently with the approaching ?fiscal cliff? and the possibility of a double-dip recession. To find remedies, they?ve examined past financial crises that were followed by protracted economic downturns. In the US, the precedent studied and cited most frequently has been the Great Depression of the 1930s, including the double dip of 1938. Unfortunately, economists have produced a variety of inconsistent explanations for both the initial contraction and the prolonged period without a self-sustained recovery.

In a relatively recent development, economists examining the Great Depression have explored the role of non-monetary financial factors, such as defaults, wealth effects and informational asymmetries, to explain why it took until 1944 for the economy to return to the level of real income seen in 1929. The research has been focused on the balance sheets of banks and businesses. With the advent of the lost decades in Japan, economists have paid even more attention to the balance sheets of financial institutions. The recession of 2007 in the US is widely viewed as a ?balance sheet recession? with the focus again on the balance sheets of financial institutions and commercial enterprises. Non-conventional monetary policies have been adopted at least in part because of the belief that a balance sheet recession reflects capital market imperfections that have rendered the normal monetary policy transmission mechanism inoperative.

In a 1978 Journal of Economic History article titled ?The Household Balance Sheet and the Great Depression,? Mishkin noted ?? the status of the household balance sheet has received little emphasis.? And it has received little attention since 2007 except for occasional calls for debt relief.

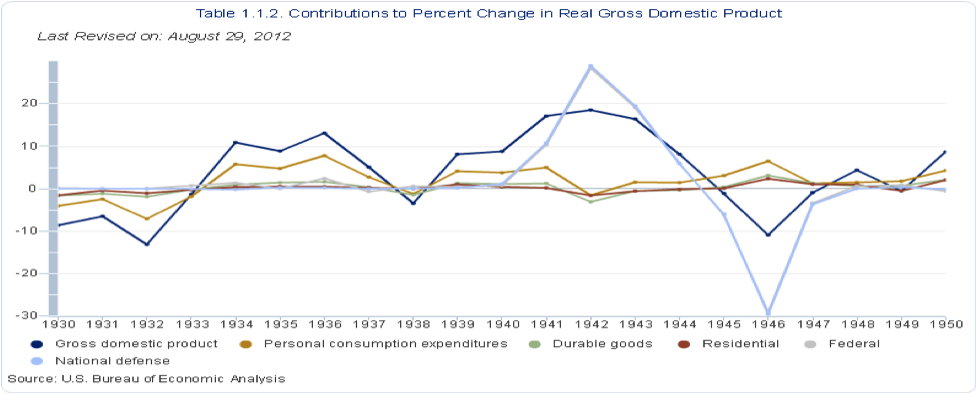

The scant attention paid to the household sector balance sheet may come with a cost. The accompanying chart shows the importance of counter-cyclical increases in consumption expenditures and residential investment immediately after WWII. These unusual counter-cyclical increases in demand helped stabilize the economy, as Federal expenditures were falling. These increases in consumption expenditures and residential investment were driven by rebuilt household balance sheets (click to enlarge).

This perspective has implications for policy when a recession or financial crisis significantly damages the household sector?s balance sheet. In those cases, stimulating the economy in the short-run by reducing savings, increasing consumer expenditure on durable goods, and increasing debt loads are counterproductive in the medium-to-long?run. Yet a number of programs designed to combat the Great Recession fall into this group. These policies include ?Cash for Clunkers,? which encouraged households to decrease savings, stock up on automobiles (a durable good), increase their debt load, and increase their ratio of real-to-financial assets. It also includes interest rate policy that discourages current savings and forces many to draw down on savings accumulated over a lifetime, thereby reducing income and consumption in the future. These policy-induced changes in household balance sheets make it less likely that, in the future, consumption demand will be able to offset the drag resulting from fiscal retrenchment.

A number of factors are responsible for the failure to consider the contribution of the household balance sheet to economic performance, especially prior to 1950. First, household balance sheets are determined by a host of macroeconomic variables, therefore the behavior of balance sheets cannot be viewed as an independent cause of changes in economic performance. However, the repair of household balance sheets can still be a necessary precursor to a recovery from a balance sheet recession, especially when the economy faces a ?fiscal cliff .?

Second, the data prior to 1950 is limited. Goldsmith, Lipsey and Mendelson (NBER 1963) constructed estimates of the ?National Balance Sheet? for selected years prior to 1945 and for each subsequent year until 1958. A more complete picture of the behavior of household balance sheets between 1922 and 1949 can be put together by employing annual observations or estimates of investment in residential real estate, the average age of the housing stock, the number of passenger cars registered, and household sector savings. While the quantity and quality of the data is such that it cannot definitively answer the questions posed by economists and historians, the exercise will provide an additional perspective on the behavior of the household balance sheet and its link with economic performance in the post-war period.

Third, much of the data that exists is not inflation adjusted. Comparisons and analyses would be easier and more informative if the series were all ?real? adjusted by an appropriate price index or deflator.

In summary, the financial position of households changed dramatically between 1929 and 1949. Consumer debt and household mortgage debt both fell in nominal terms between 1929 and 1933. Between 1933 and 1939, consumer debt more than doubled, but mortgage debt managed a mere 6+% increase. In total, the two forms of debt increased by approximately 27.5%. From 1939 to 1945, the increase in consumer and mortgage debt was less than 2%. Between 1945 and 1949, consumer debt more than tripled and mortgage debt more than doubled.

The asset side of the household sector?s balance sheet also saw dramatic changes. The value of equity investments plunged between 1929 and 1933. Equity holdings had not returned to the 1929 peak (in either nominal or real terms) by 1949. The value of other asset holdings behaved differently. Between 1939 and 1945, Currency and demand Deposits increased by almost 250% and then drifted lower between1945 and 1949. The household sector?s holdings of federal government securities increased by over 600% between 1939 and 1945. Holdings of government securities drifted sideways between 1945 and 1949 to end the period on balance lower. Real assets were also affected. Data in the Historical Statistics of the United States and the Statistical Abstract of the United States confirms that the average age of the housing increased from 1928 until 1945 and consumer durables moved in line with the economy until the war and grew dramatically after the war.

The change in the behavior of households is perhaps most dramatically reflected in the changes in household savings. When measured as a percentage of disposable income, US households saved 4-5x as much during the years between 1941 and 1945 as they had at their peak in 1929 and 3-4x as much as they did in the post-war period (click to enlarge).

By the end of the war, the household sector?s balance sheet asset mix had been recast. Households had increased their holdings of safe, liquid financial assets, while economic dislocations prior to the war, rationing during the war, and depreciation resulted in declines in real assets (click to enlarge).

During the recession of 1938, consumption expenditures and residential investment declined, yet they expanded during the recessions of 1945 and 1949. These post-WWII counter-cyclical increases in consumption expenditures and residential investment suggest that the recasting of the household sector?s balance sheet helped insulate the economy from the fiscal cliff at the war?s end. However, given that economists and historians have been unable to arrive at an agreed-upon explanation for the depth and length of the Great Depression and the fact that balance sheets are endogenous, it would be a mistake to view the improvement in household balance sheets as a complete explanation of the emergence of a post-war self-sustained recovery. Nonetheless, the behavior of the household sector?s balance sheet sheds some light on the wisdom of economic policies aimed at producing a recovery from a recession in which the household sector?s balance sheet has been damaged. This is especially relevant when the recovery must be self-sustaining given impending fiscal retrenchment.

Despite the dramatic and sudden fiscal retrenchment post-WWII, the US economy only experienced an 8-month long recession in 1945,. However, the authorities may actually face a greater challenge now than they faced then. After the war, US households were both willing and able to increase consumption relative to GDP. During the war, consumption as a percentage of GDP was well below its historical average. The end of war time rationing and shortages allowed consumption to mean revert. Tax receipts declined by about of 5% of GDP between 1944 and 1947. This served to increase disposable income and consumption relative to GDP. The personnel savings rate had been well above the average during the war. This forced savings during the war left the household sector with greatly increased holdings of liquid bank deposits and government securities. The household sector was clearly financially able and willing to increase current consumption, its holdings of consumer durables and its debt load, as well as to demand new and better consumer durables and housing.

Today, consumption remains above its post-war average as a percentage of GDP. The likelihood of pent-up demand buoying consumption expenditures is remote and any reversion to the mean will reduce consumption. Given the recent popping of the housing bubble, it is unlikely that household sector demand will drive an increase in residential real estate investment such as the increase that occurred after WWII. Furthermore, the probability of tax receipts falling as a percentage of GDP and thus supporting disposable income and consumption is remote and inconsistent with fiscal retrenchment. During WWII, policy forced increased savings and a rebuilding of household balance sheets. Recent policy created negative after-tax real rates of return, discouraged savings and promoted the purchase of durable goods. Recoveries in household financial assets have been dominated by recoveries in the value of real estate and equity prices, but it is unlikely that households will increase spending based upon unrealized gains in real estate and equity assets as they did prior to the tech and housing bubbles.

Assuming a fiscal retrenchment, balance-sheet-driven increases in consumption relative to GDP will have to carry a much larger share of the burden than they carried after WWII, if the economy is to grow. Assuming a decline in demand from the government sector (19.5% of GDP) as part of fiscal retrenchment and a decline in consumption demand (71+%) as a result of mean reversion and the fiscal retrenchment (higher taxes and lower transfer payments), then GDP growth will depend upon the remaining components of demand (9.5%) growing quickly enough to more than offset the decline in demand by the household and government sectors (90.5%).

To the extent that macroeconomic policies since 2007 have contributed to recent increases in economic activity and declines in unemployment by preventing the rehabilitation of the household sector?s balance sheet, they have done so at the expense of delaying the return to a self-sustained economic expansion. These policies may ultimately contribute to a Japan-like outcome for the US: years and years of slow growth with an economy dependent on larger budget deficits and continuous extraordinary monetary policy. The policies have not solved the macroeconomic economic problem facing the country, but rather postponed and perhaps increased the ultimate cost of the required adjustments.

Less formally, can monetary policy, which rebuilds the balance sheets of financial intermediaries at the expense of the balance sheets of households and other economic agents they intermediate between, really be the path to lasting recovery?

super bowl 2012 kickoff time football score ron paul nevada buffalo chicken dip super bowl 2012 soul train nevada caucus

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.